wCorr Formulas

Paul Bailey, Ahmad Emad, Ting Zhang, Qingshu Xie

2023-08-18

Source:vignettes/wCorrFormulas.Rmd

wCorrFormulas.RmdThe wCorr package can be used to calculate Pearson, Spearman, polyserial, and polychoric correlations, in weighted or unweighted form.1 The package implements the tetrachoric correlation as a specific case of the polychoric correlation and biserial correlation as a specific case of the polyserial correlation. When weights are used, the correlation coefficients are calculated with so called sample weights or inverse probability weights.2

This vignette introduces the methodology used in the wCorr package for computing the Pearson, Spearman, polyserial, and polychoric correlations, with and without weights applied. For the polyserial and polychoric correlations, the coefficient is estimated using a numerical likelihood maximization.

The weighted (and unweighted) likelihood functions are presented. Then simulation evidence is presented to show correctness of the methods, including an examination of the bias and consistency. This is done separately for unweighted and weighted correlations.

Numerical simulations are used to show:

- The bias of the methods as a function of the true correlation coefficient (\(\rho\)) and the number of observations (\(n\)) in the unweighted and weighted cases; and

- The accuracy [measured with root mean squared error (RMSE) and mean absolute deviation (MAD)] of the methods as a function of \(\rho\) and \(n\) in the unweighted and weighed cases.

Note that here bias is used for the mean difference between true correlation and estimated correlation.

The wCorr Arguments vignette describes the effects the

ML and fast arguments have on computation and

gives examples of calls to wCorr.

Specification of estimation formulas

Here we focus on specification of the correlation coefficients between two vectors of random variables that are jointly bivariate normal. We call the two vectors X and Y. The \(i^{th}\) members of the vectors are then called \(x_i\) and \(y_i\).

Formulas for Pearson correlations with and without weights

The weighted Pearson correlation is computed using the formula \[r_{Pearson}=\frac{\sum_{i=1}^n \left[ w_i (x_i-\bar{x})(y_i-\bar{y}) \right]}{\sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^n \left( w_i (x_i-\bar{x})^2 \right)\sum_{i=1}^n \left( w_i (y_i-\bar{y})^2 \right) }} \]

where \(w_i\) is the weights, \(\bar{x}\) is the weighted mean of the X variable (\(\bar{x}=\frac{1}{\sum_{i=1}^n w_i}\sum_{i=1}^n w_i x_i\)), \(\bar{y}\) is the weighted mean of the Y variable (\(\bar{y}=\frac{1}{\sum_{i=1}^n w_i}\sum_{i=1}^n w_i y_i\)), and \(n\) is the number of elements in X and Y.3

The unweighted Pearson correlation is calculated by setting all of the weights to one.

Formulas for Spearman correlations with and without weights

For the Spearman correlation coefficient the unweighted coefficient is calculated by ranking the data and then using those ranks to calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient–so the ranks stand in for the X and Y data. Again, similar to the Pearson, for the unweighted case the weights are all set to one.

For the unweighted case the highest rank receives a value of 1 and the second highest 2, and so on down to the \(n\)th value. In addition, when data are ranked, ties must be handled in some way. The chosen method is to use the average of all tied ranks. For example, if the second and third rank units are tied then both units would receive a rank of 2.5 (the average of 2 and 3).

For the weighted case there is no commonly accepted weighted Spearman correlation coefficient. Stata does not estimate a weighted Spearman and SAS does not document their methodology in either of the corr or freq procedures.

The weighted case presents two issues. First, the ranks must be calculated. Second, the correlation coefficient must be calculated.

Calculating the weighted rank for an individual level is done via two terms. For the \(j\)th element the rank is

\[rank_j = a_j + b_j\]

The first term \(a_j\) is the sum of all weights W less than or equal to this value of the outcome being ranked (\(\xi_j\))

\[a_j = \sum_{i=1}^n w_i \mathbf{1}\left( \xi_i < \xi_j \right)\]

where \(\mathbf{1}(\cdot)\) is the indicator function that is one when the condition is true and 0 when the condition is false, \(w_i\) is the \(i\)th weight and \(\xi_i\) and \(\xi_j\) are the \(i\)th and \(j\)th value of the vector being ranked, respectively.

The term \(b_j\) then deals with ties. When there are ties each unit receives the mean rank for all of the tied units. When the weights are all one and there are \(n\) tied units the vector of tied ranks would be \(\mathbf{v}=\left(a_j+1, a_j+2, \dots, a_j+n \right)\). The mean of this vector (here called \(rank^1\) to indicate it is a specific case of \(rank\) when the weights are all one) is then

\[rank_j^1=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \left(a_j + i \right)\] \[=\frac{1}{n} \left( n a_j + \frac{n(n+1)}{2} \right)\] \[=a_j + \frac{n+1}{2}\]

thus

\[b_j^1=\frac{n+1}{2}\]

where the superscript one is again used to indicate that this is only for the unweighted case where all weights are set to one.

For the weighted case this could be \(\mathbf{v}=\left(a_j+w_1', a_j+w_1'+w_2', \dots, a_j+\sum_{k=1}^n w_k' \right)^T\) where W’ is a vector containing the weights of the tied units. It is readily apparent that the mean of this vector value will depend on the ordering of the weights. To avoid this, the overall mean of all possible permutations of the weights is calculated. The following formula does just that

\[b_j = \frac{n+1}{2}\bar{w}_j\]

where \(\bar{w}_j\) is the mean weight of all of the tied units. It is easy to see that when the weights are all one \(\bar{w}_j=1\) and \(b_j = b_j^1\). The latter (more general) formula is used for all cases.

After the X and Y vectors are ranked they are plugged into the weighted Pearson correlation coefficient formula shown earlier.

##Formulas for polyserial correlation with and without weights For the polyserial correlation, it is again assumed that there are two continuous variables X and Y that have a bivariate normal distribution.4

\[\begin{pmatrix} X \\ Y \end{pmatrix} \sim N \left[ \begin{pmatrix} \mu_x \\ \mu_y \end{pmatrix}, \boldsymbol{\Sigma} \right]\]

where \(N(\mathbf{A},\boldsymbol{\Sigma})\) is a bivariate normal distribution with mean vector A and covariance matrix \(\boldsymbol{\Sigma}\). For the polyserial correlation, Y is discretized into the random variable M according to

\[m_i= \begin{cases} 1 \quad \mathrm{if} \theta_2 < y_i < \theta_3 \\ 2 \quad \mathrm{if} \theta_3 < y_i < \theta_4 \\ \vdots \\ t \quad \mathrm{if} \theta_{t+1} < y_i < \theta_{t+2} \end{cases}\]

where \(\theta\) indicates the cut points used to discretize Y into M, and \(t\) is the number of bins. For notational convenience, \(\theta_2 \equiv -\infty\) and \(\theta_{t+2} \equiv \infty\).5

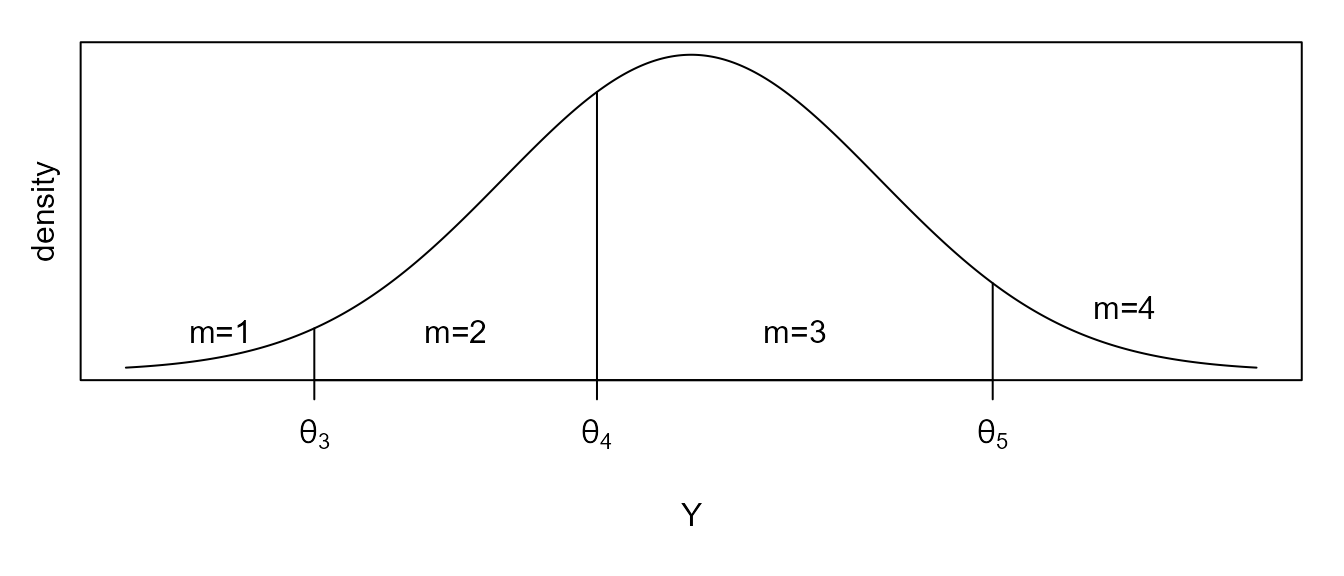

To give a concrete example, the following figure shows the density of Y when the cuts points are, for this example, \(\theta=\left(-\infty,-2,-0.5,1.6,\infty\right)\). In this example, any value of \(-2 < y_i < -0.5\) would have \(m_i=2\).

Figure 1 :. Density of Y for cutpoints \(\theta = (-\infty, -2, -0.5, 1.6, \infty\)).

hi

Figure 1 :. Density of Y for cutpoints \(\theta = (-\infty, -2, -0.5, 1.6,

\infty\)).

Notice that \(\mu_y\) is not identified (or is irrelevant) because, for any \(a \in \mathbb{R}\), setting \(\tilde{\mu}_y = \mu_y + a\) and \(\tilde{\boldsymbol{\theta}}=\boldsymbol{\theta} + a\) lead to exactly the same values of \(\mathbf{M}\) and so one of the two must be arbitrarily assigned. A convenient decision is to decide \(\mu_y \equiv 0\). A similar argument holds for \(\sigma_y\) so that \(\sigma_y \equiv 1\).

For X, Cox (1974) observes that the MLE mean and standard deviation of X are simply the average and (population) standard deviation of the data and do not depend on the other parameters.6 This can be taken advantage of by defining \(z\) to be the standardized score of \(x\) so that \(z \equiv \frac{x- \bar{x}}{ \hat\sigma_x}\).

Combining these simplifications, the probability of any given \(x_i\), \(m_i\) pair is

\[\mathrm{Pr}\left( \rho=r, \boldsymbol{\Theta}=\boldsymbol{\theta} ; Z=z_i, M=m_i \right) = \phi(z_i) \int_{\theta_{m_i+1}}^{\theta_{m_i+2}} \!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\! f(y|Z=z_i,\rho=r)dy\]

where \(\mathrm{Pr}\left( \rho=r, \boldsymbol{\Theta}=\boldsymbol{\theta}; Z=z_i, M=m_i \right)\) is the probability of the event \(\rho=r\) and the cuts points are \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\), given the \(i\)th data point \(z_i\) and \(m_i\); \(\phi(\cdot)\) is the standard normal; and \(f(Y|Z,\rho)\) is the distribution of Y conditional on Z and \(\rho\). Because Y and Z are jointly normally distributed (by assumption) \[f(Y|Z=z_i,\rho=r) =N\left(\mu_y + \frac{\sigma_y}{\sigma_z}r(z_i-\mu_z), (1-r^2){\sigma_y}^2 \right)\] because both Z and Y are standard normals \[f(y|Z=z_i,\rho=r) =N\left(r \cdot z_i, (1-r^2) \right)\] Noticing that \(\frac{y-r\cdot z}{\sqrt{1-r^2}}\) has a standard normal distribution \[\mathrm{Pr}\left( \rho=r, \boldsymbol{\Theta}=\boldsymbol{\theta} ; Z=z_i, M=m_i \right) = \phi(z_i) \left[ \Phi\left( \frac{\theta_{m_i+2} - r \cdot z_i}{\sqrt{1-r^2}} \right) - \Phi \left( \frac{\theta_{m_i+1} - r \cdot z_i}{\sqrt{1-r^2}} \right) \right]\]

where \(\Phi(\cdot)\) is the standard normal cumulative density function. Using the above probability function as an objective, the log-likelihood is then maximized. \[\ell(\rho=r, \boldsymbol{\Theta}=\boldsymbol{\theta};\mathbf{Z}=\mathbf{z},\mathbf{M}=\mathbf{m}) = \sum_{i=1}^n w_i \ln\left[ \mathrm{Pr}\left( \rho=r, \boldsymbol{\Theta}=\boldsymbol{\theta} ; Z=z_i, M=m_i \right) \right]\] where \(w_i\) is the weight of the \(i^{th}\) members of the vectors Z and Y. For the unweighted case, all of the weights are set to one.

The value of the nuisance parameter \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) is chosen to be

\[\hat{\theta}_{j+2} = \Phi^{-1}(n/N)\]

where \(n\) is the number of values to the left of the \(j\)th cut point (\(\theta_{j+2}\) value) and \(N\) is the number of data points overall. Here two is added to \(j\) to make the indexing of \(\theta\) agree with Cox (1974) as noted before. For the weighted cause \(n\) is replaced by the sum of the weights to the left of the \(j\)th cut point and \(N\) is replaced by the total weight of all units

\[\hat{\theta}_{j+2} = \Phi^{-1}\left( \frac{\sum_{i=1}^N w_i \mathbf{1}(m_i < j) }{\sum_{i=1}^N w_i} \right)\]

where \(\mathbf{1}\) is the indicator function that is 1 when the condition is true and 0 otherwise.

###Computation of polyserial correlation For the polyserial,

derivatives of \(\ell\) can be written

down but are not readily computed. When the ML argument is

set to FALSE (the default), a one dimensional optimization

of \(\rho\) is calculated using the

optimize function in the stats package and the

values of \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) from

the previous paragraph. When the ML argument is set to

TRUE, a multi-dimensional optimization is done for \(\rho\) and \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) using the

bobyqa function in the minqa package. See the

wCorr Arguments vignette for a comparison of these two

methods.

Because the numerical optimization is not perfect when the correlation is in a boundary condition (\(\rho \in \{-1,1\}\)), a check for perfect correlation is performed before the above optimization by simply examining if the values of X and M have agreeing order (or opposite but agreeing order) and then the MLE correlation of 1 (or -1) is returned.

##Methodology for polychoric correlation with and without weights

Similar to the polyserial correlation, the polychoric correlation is a simple case of two continuous variables X and Y that have a bivariate normal distribution. In the case of the polyserial correlation the continuous (latent) variable Y was observed as a discretized variable M. For the polychoric correlation, this is again true but now the continuous (latent) variable X is observed as a discrete variable P according to

\[p_i= \begin{cases} 1 \quad \mathrm{if} \theta'_2 < x_i < \theta'_3 \\ 2 \quad \mathrm{if} \theta'_3 < x_i < \theta'_4 \\ \vdots \\ t \quad \mathrm{if} \theta'_{t'+1} < x_i < \theta'_{t'+2} \end{cases}\]

where \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) remains the cut points for the distibution defining the transformation of Y to M, \(\boldsymbol{\theta}'\) is the cut points for the transformation from X to P, and \(t'\) is the number of bins for P. Similar to \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\), \(\boldsymbol{\theta}'\) has \(\theta'_2 \equiv -\infty\) and \(\theta'_{t'+2} \equiv \infty\).

As in the polyserial correlation, \(\mu_y\) is not identified (or is irrelevant) because, for any \(a \in \mathbb{R}\), setting \(\tilde{\mu}_y = \mu_y + a\) and \(\tilde{\boldsymbol{\theta}}=\boldsymbol{\theta} + a\) lead to exactly the same values of \(\mathbf{M}\) and so one of the two must be arbitrarily assigned. The same is true for \(\mu_x\). A convenient decision is to decide \(\mu_y = \mu_x \equiv 0\). A similar argument holds for \(\sigma_y\) and \(\sigma_x\) so that \(\sigma_y = \sigma_x \equiv 1\)

Then the probability of any given \(m_i\), \(p_i\) pair is

\[\mathrm{Pr}\left( \rho=r, \boldsymbol{\Theta}=\boldsymbol{\theta}, \boldsymbol{\Theta}'=\boldsymbol{\theta}' ; P=p_i, M=m_i \right) = \int_{\theta'_{p_i+1}}^{\theta'_{p_i+2}} \int_{\theta_{m_i+1}}^{\theta_{m_i+2}} \!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\! f(x,y|\rho=r)dydx\]

where \(\rho\) is the correlation coefficient.

Using this function as an objective, the log-likelihood is then maximized. \[\ell(\rho=r, \boldsymbol{\Theta}=\boldsymbol{\theta}, \boldsymbol{\Theta}'=\boldsymbol{\theta}';\mathbf{P}=\mathbf{p},\mathbf{M}=\mathbf{m}) = \sum_{i=1}^n w_i \ln\left[\mathrm{Pr}\left( \rho=r, \boldsymbol{\Theta}=\boldsymbol{\theta}, \boldsymbol{\Theta}'=\boldsymbol{\theta}' ; P=p_i, M=m_i \right) \right] \]

This is the weighted log-likelihood function. For the unweighted case all of the weights are set to one.

###Computation of polychoric correlation This again mirrors the

treatment of the polyserial. The derivatives of \(\ell\) for the polychoric can be written

down but are not readily computed. When the ML argument is

set to FALSE (the default), a one dimensional optimization

of \(\rho\) is calculated using the

optimize function from the stats package and

values of \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) and

\(\boldsymbol{\theta}'\) are

computed using the last equation in the section titled, “Formulas for

polyserial correlation with and without weights”. When the

ML argument is set to TRUE a multi-dimensional

optimization is done for \(\rho\),

\(\boldsymbol{\theta}\), and \(\boldsymbol{\theta}'\) using the

bobyqa function in the minqa package. See the

wCorr Arguments vignette for a comparison of these two

methods.

Because the optimization is not perfect when the correlation is in a boundary condition (\(\rho \in \{-1,1\}\)), a check for perfect correlation is performed before the above optimization by simply examining if the values of P and M have a Goodman-Kruskal correlation coefficient of -1 or 1. When this is the case, the MLE of -1 or 1, respectively, is returned.

#Simulation evidence on the correctness of the estimating methods

It is easy to prove the consistency of the \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) for the polyserial correlation and \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) and \(\boldsymbol{\theta}'\) for the polychoric correlation using the non-ML case. Similarly, for \(\rho\), because it is an MLE that can be obtained by taking a derivative and setting it equal to zero, the results are asymptotically unbiased and obtain the Cramer-Rao lower bound.

This does not speak to the small sample properties of these correlation coefficients. Previous work has described their properties by simulation; and that tradition is continued below.7

Simulation study of unweighted correlations

In what follows, when the exact method of selecting a parameter (such as \(n\)) is not noted in the above descriptions it is described as part of each simulation.

Across a number of iterations (the exact number of times will be stated for each simulation), the following procedure is used:

- select a true Pearson correlation coefficient \(\rho\);

- select the number of observations \(n\);

- generate X and Y to be bivariate normally distributed using a pseudo-Random Number Generator (RNG);

- using a pseudo-RNG, select the number of bins for M and P (\(t\) and \(t'\)) independantly from the set {2, 3, 4, 5};8

- select the bin boundaries for M and P (\(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) and \(\boldsymbol{\theta}'\)) by sorting the results of \((t-1)\) and \((t'-1)\) draws, respectively, from a normal distribution using a pseudo-RNG;

- confirm that at least 2 levels of each of M and P are occupied (if not, return to previous step); and

- calculate and record relevant statistics.

Bias, and RMSE of the unweighted correlations

This sections shows the bias of the correlations as a function of the true correlation coefficient, \(\rho\). To that end, a simulation was done at each level of the cartesian product of \(\rho \in \left( -0.99, -0.95, -0.90, -0.85, ..., 0.95, 0.99 \right)\), and \(n \in \{10, 100, 1000\}\). For precision, each level of \(\rho\) and \(n\) was run fifty times. The bias is the mean difference between the true correlation coefficient (\(\rho_i\)) and estimate correlation coefficient (\(r_i\)). The RMSE is the square root of the mean squared error.

\[\mathrm{RMSE}= \sqrt{ \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \left( r_i - \rho_i \right)^2 }\]

And the bias is given by

\[bias=\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n \left(r_i - \rho_i \right)\]

Figure 2 : shows the bias as a function of the true correlation \(\rho\). Only the polyserial shows no bias at any level of \(n\), shown by no clear deviation from 0 at any level of \(\rho\). For the Pearson correlation there is bias when \(n=10\) that is not present when \(n=100\) or 1,000. This is a well known property of the estimator.9 Similarly, the polychoric shows bias when \(n=10\).

The Spearman correlation shows bias at all of the tested levels of \(n\). The bias is zero when the true correlation is 1, 0, or -1; is positive when \(\rho\) is below 0 (negative correlation); and is negative when \(\rho\) is above 0 (positive correlation). In this section, the Spearman correlation coefficient is compared with the true Pearson correlation coefficient. When this is done, the bias is expected because the Spearman correlation is not intended to recover a Pearson type correlation coefficient; it is designed to measure a separate quantity.

Figure 2 :. Bias Versus \(\rho\) for Unweighted

Correlations.

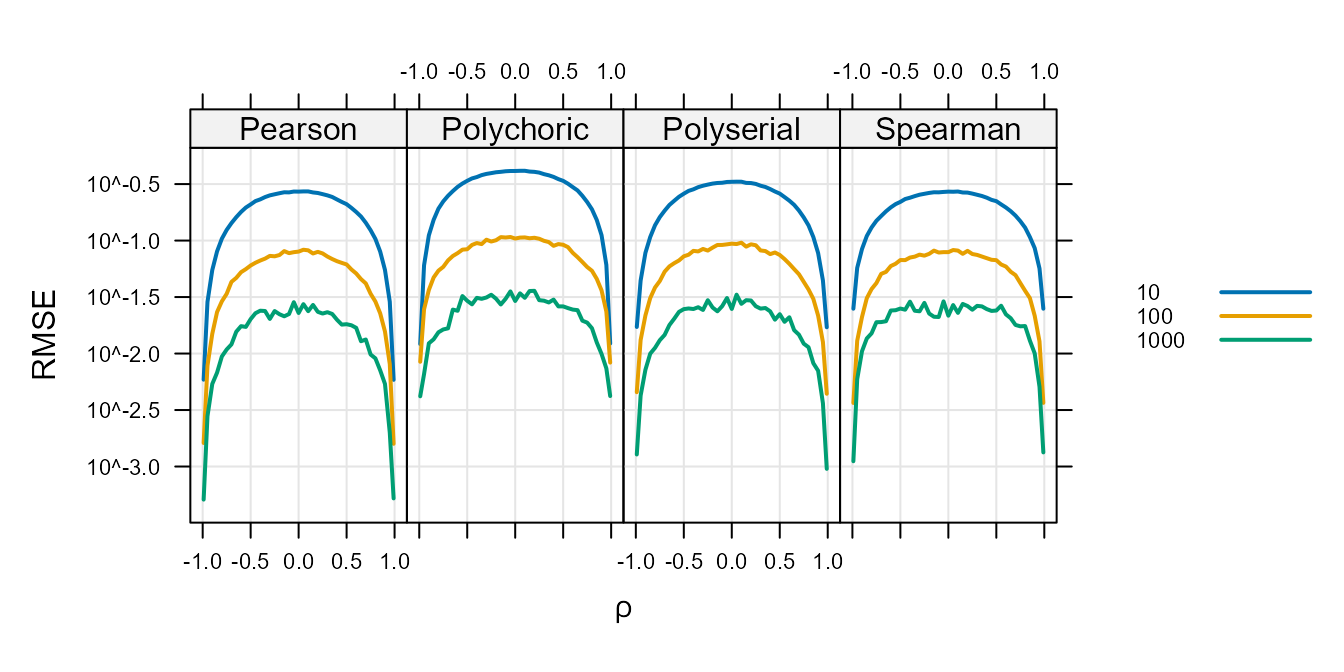

Figure 3 : shows the RMSE as a function of \(\rho\). All of the correlation coefficients have a uniform RMSE as a function of \(\rho\) near \(\rho=0\) that decreases near \(|\rho|=1\). All plots also show a decrease in RMSE as \(n\) increases. This plot shows that there is no appreciable RMSE differences as a functions of \(\rho\). In addition, it show that our attention to the MLE correlation of -1 or 1 at edge cases did not make the RMSE much worse in the neighborhood of the edges (\(|\rho| \sim 1\)).

Figure 3 :. Root Mean Square Error Versus \(\rho\) for Unweighted

Correlations.

Consistency of the correlations

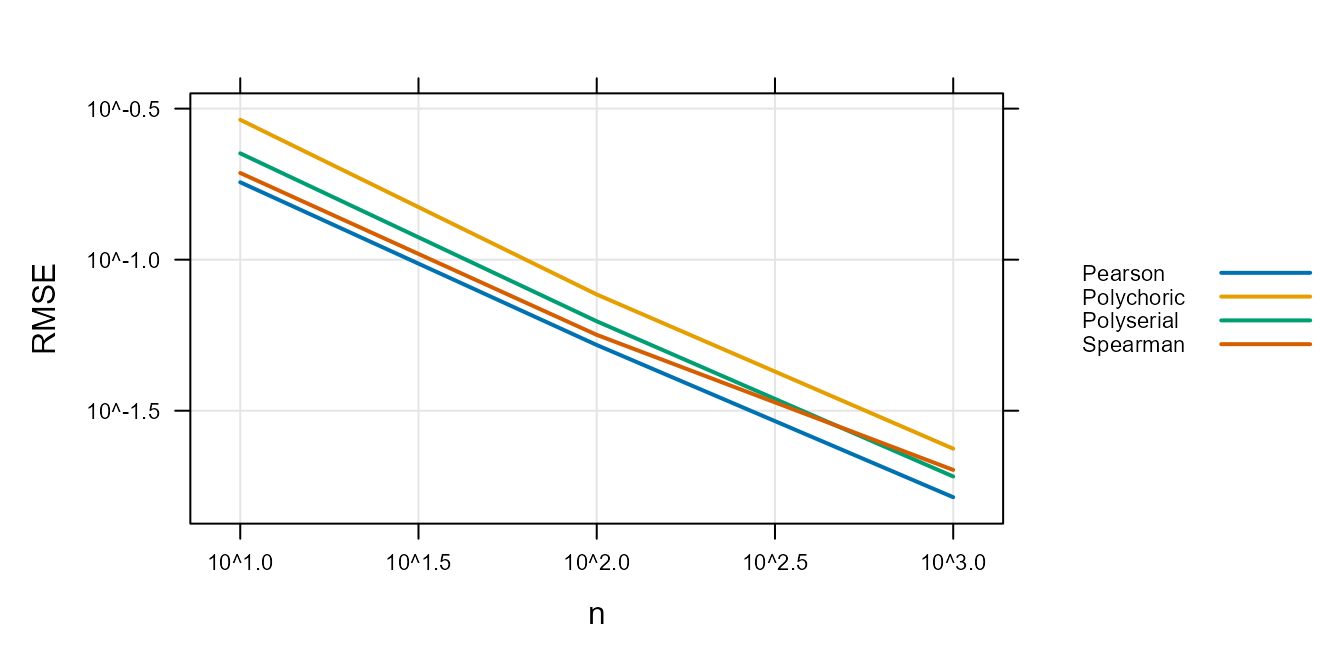

Figure 4 : shows the RMSE as a function of \(n\). The purpose of this plot is not to show an individual value but to show that the estimator is consistent. The plot shows a slope of about \(-\frac{1}{2}\) for the Pearson, polychoric, and polyserial correlations. This is consistent with the expected first order convergence for each correlation coefficient under the assumptions of this simulation. Results for the Spearman also show approximate first order convergence but the slope increases slightly as \(n\) increases. Again, the Spearman is not estimating the same quantity as the Pearson and so is expected to diverge.

The plot also shows that the RMSE is less than 0.1 for all methods when \(n>100\).

Figure 4 :. Root Mean Square Error Versus sample

size for Unweighted Correlations.

Computing Time

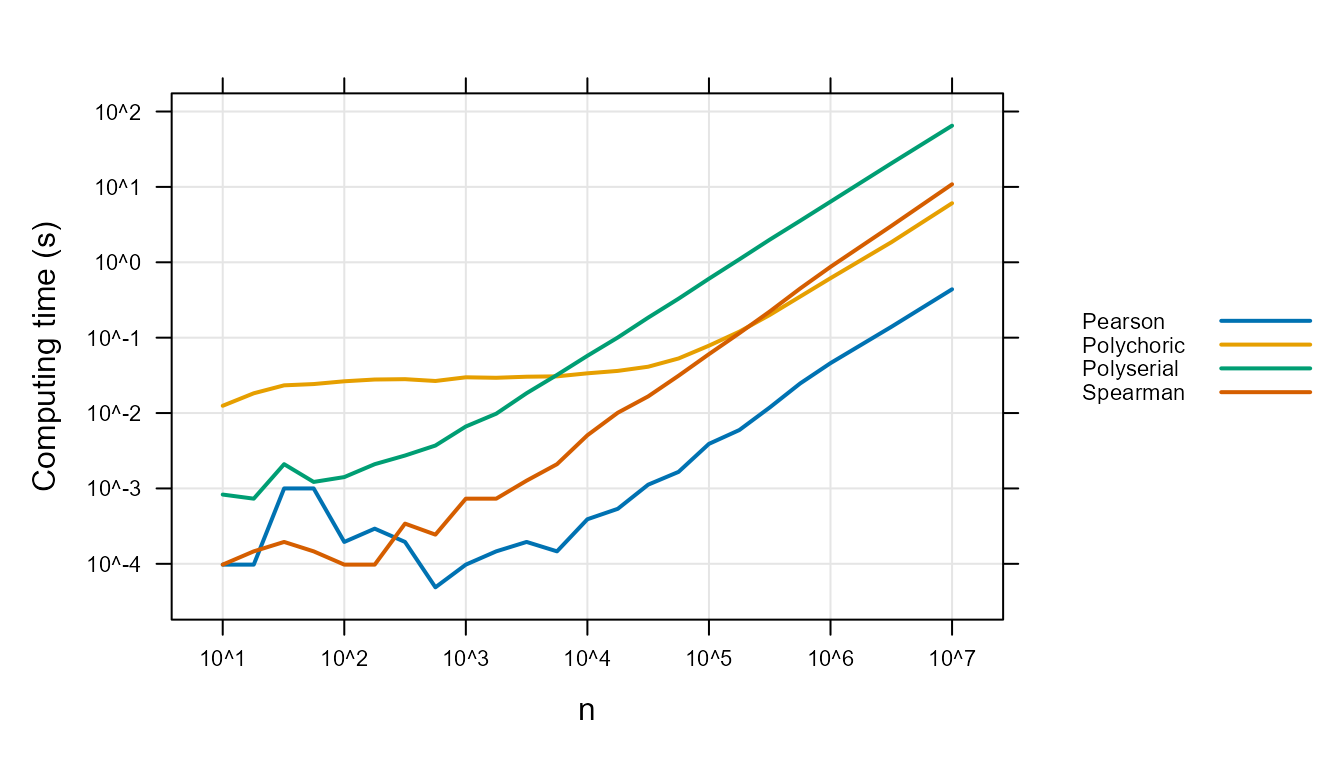

Figure 5 : shows the mean time (in seconds) to compute a single correlation coefficient as a function of \(\rho\) by \(n\) size. The plot shows linearly rising computation times with slopes of about one. This is consistent with a linear computation cost. Using Big O notation, the computation cost is, in the range shown, O(\(n\)). The slope of the Spearman is slightly faster and the algorithm has a O(\(n \mathrm{lg}(n)\)) sort involved, so this is, again, expected.

Figure 5 :. Computation time.

Simulation study of weighted correlations

When complex sampling (other than simple random sampling with replacement) is used, unweighted correlations may or may not be consistent. In this section the consistency of the weighted coefficients is examined.

When generating simulated data, decisions about the generating functions have to be made. These decisions affect how the results are interpreted. For the weighted case, if these decisions lead to something about the higher weight cases being different from the lower weight cases then the test will be more informative about the role of weights. Thus, while it is not reasonable to always assume that there is a difference between the high and low weight cases, the assumption (used in the simulations below) that there is an association between weights and the correlation coefficients serves as a more robust test of the methods in this package.

##Results of weighted correlation simulations

Simulations are carried out in the same fashion as previously described but include a few extra steps to accommodate weights. The following changes were made:

- Weights are assigned according to \(w_i = (x-y)^2 + 1\), and the probability of inclusion in the sample was then \(Pr_i = \frac{1}{w_i}\).

- For each unit, a uniformly distributed random number was drawn. When that value was less than the probability of inclusion (\(Pr_i\)), the unit was included.

Units were generated until \(n\) units were in the sample.

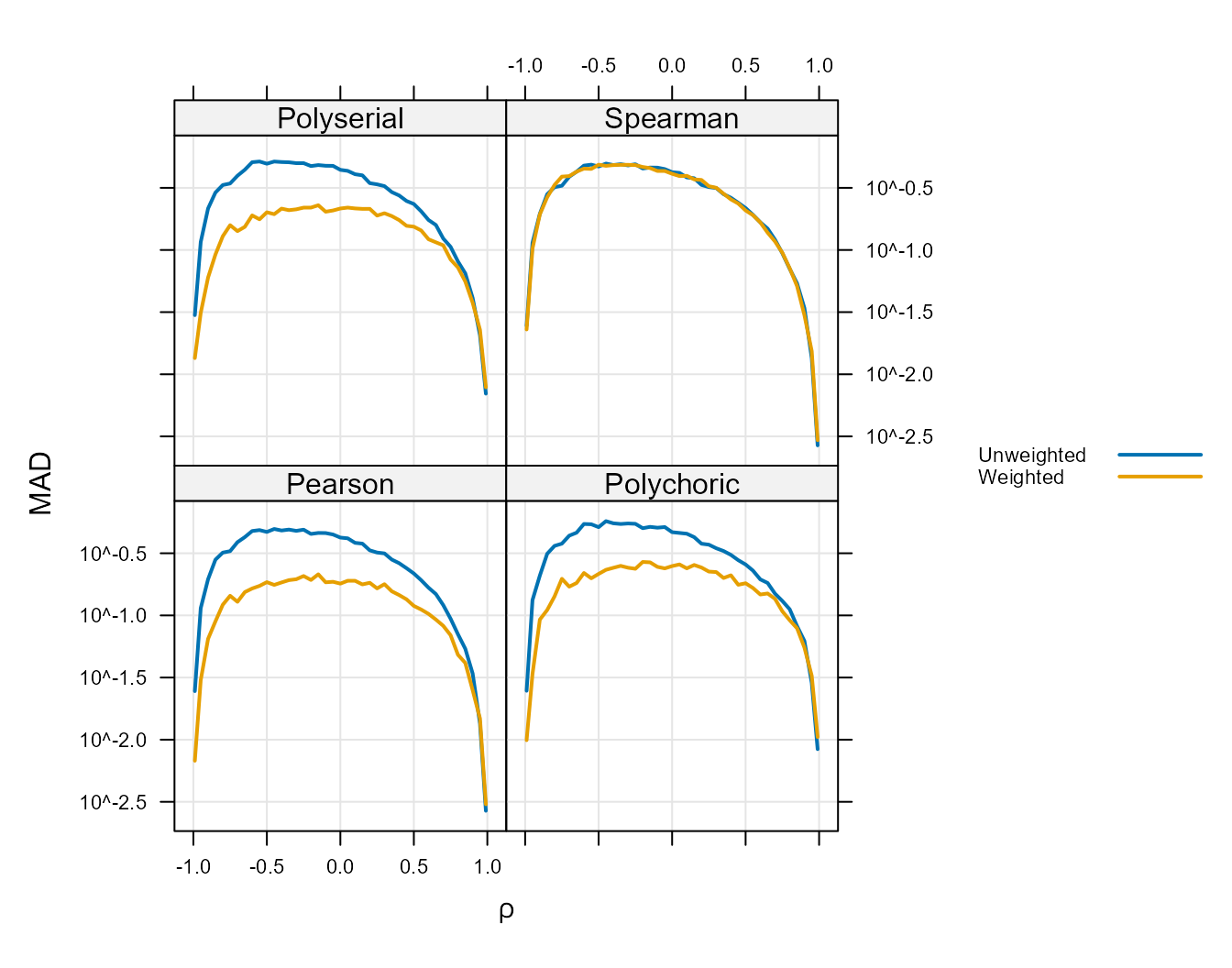

Two simulations were run. The first shows the mean absolute deviation (MAD)

\[MAD=\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n |r_i - \rho_i|\]

as a function of \(\rho\) and was run for \(n=100\) and \(\rho \in \left( -0.99, -0.95, -0.90, -0.85, ..., 0.95, 0.99 \right)\), with 100 iterations run for each value of \(\rho\).

The following plot shows the MAD for the weighted and unweighted results as a function of \(\rho\) when \(n=100\). This shows that for values of \(\rho\) near zero, under our simulation assumptions (for all but the Spearman correlation) the weighted correlation performs better than (that is, has lower MAD than) the unweighted correlation for all correlation coefficients. Over the entire range, the difference between the two is never such that the unweighted has a lower MAD. Thus, under the simulated conditions at least, the weighted correlation has lower or approximately equal MAD for every value of the true correlation coefficient (\(\rho\)).

Figure 6 :. Mean Absolute Deviation Versus \(\rho\) (Weighted).

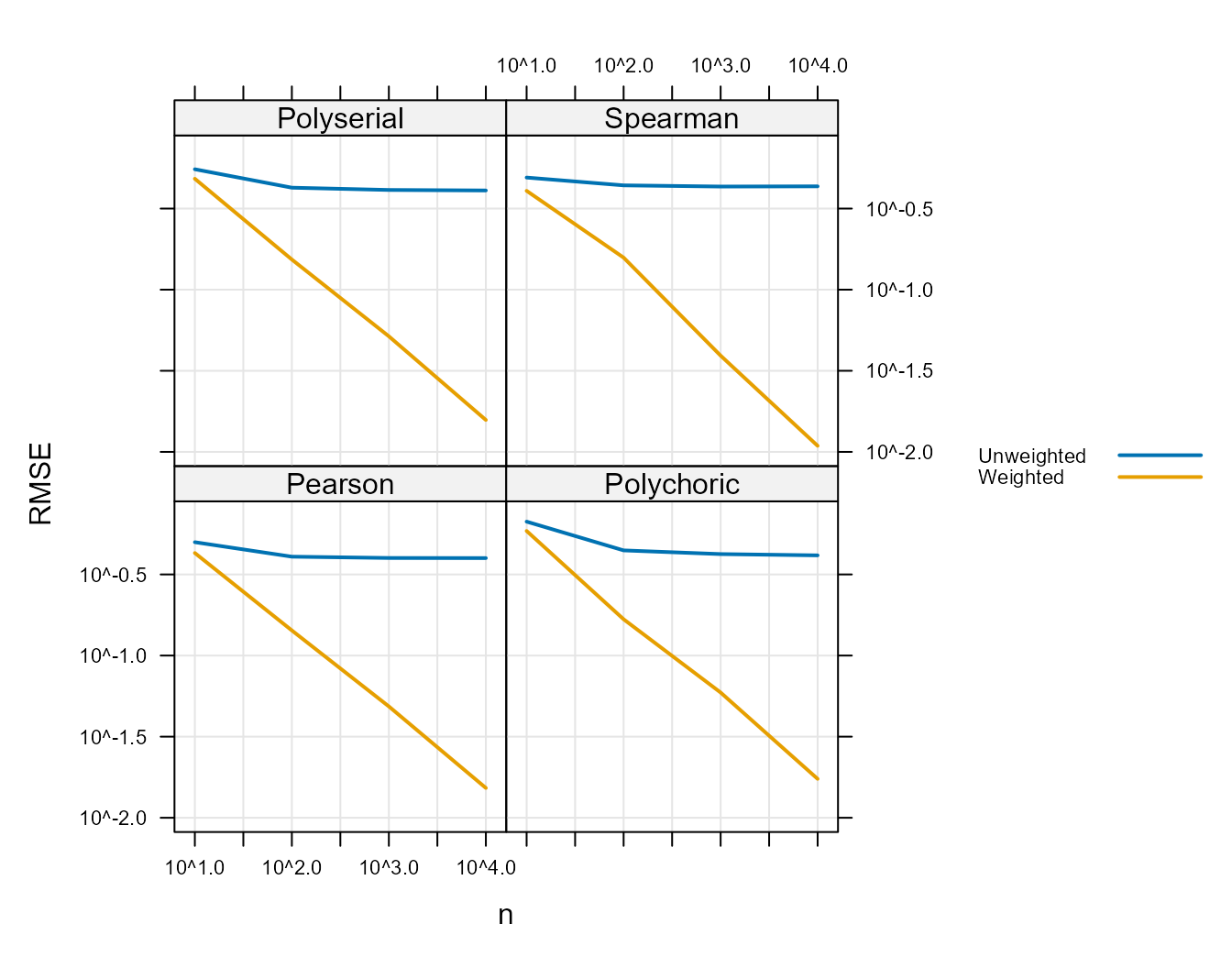

The second simulation (shown in Figure 7 :) used the same values of \(\rho\) and used \(n \in \{10, 100, 1000, 10000 \}\) and shows how RMSE and sample size are related. In particular, it shows first-order convergence of the weighted Pearson, polyserial, and polychoric correlation coefficient.

For the previous plots the calculated Spearman correlation coefficient was compared to the generating Pearson correlation coefficient. For this plot only, the Spearman correlation coefficient to the true Spearman correlation coefficient. This is because the Spearman coefficient is not attempting to estimate the Pearson correlation. To do this the simulation is modified slightly. A population of data is generated and the true Spearman correlation coefficient then is calculated as the population coefficient.10 Then, a sample from the population with varying probability as described in the weighted simulation section is used to calculate sample Spearman correlation coefficient. Then the root mean squared difference between the sample and population coefficients are calculated as with the Pearson–except that the population Spearman correlation coefficient is used in place of the Pearson correlation coefficient (\(\rho\)).

Thus, the results in Figure 7 : show that, when compared to the true Spearman correlation coefficient, the weighted Spearman correlation coefficient is consistent.

In all cases the RMSE is lower for the weighted than the unweighted. Again, the fact that the simulations show that the unweighted correlation coefficient is not consistent does not imply that it will always be that way–only that this is possible for these coefficients to not be consistent.

Figure 7 :. Root Mean Square Error Versus \(\rho\) (Polyserial, Pearson, Polychoric

panels) or Population Spearman correlation coefficient (Spearman panel)

for Weighted Correlations

#Conclusion Overall the simulations show first order convergence for each unweighted correlation coefficient with an approximately linear computation cost. Further, under our simulation assumptions, the weighted correlation performs better than (has lower MAD or RMSE than) the unweighted correlation for all correlation coefficients.

We show the first order convergence of the weighted Pearson, polyserial, and polychoric correlation coefficient. The Spearman is shown to not consistently estimate the population Pearson correlation coefficient but is shown to consistently estimate the population Spearman correlation coefficient–under the assumptions of our simulation.

Appendix Proof of consistency of Horvitz-Thompson (HT) estimator of a mean

An HT estimator of a sum takes the form \[\hat{Y} = \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{1}{\pi_i} y_i\] where there are \(n\) sampled units from a population of \(N\) units, each unit has a value \(y\in R\), each unit is sampled with probability \(\pi_i\), and \(\hat{Y}\) is the estimated of \(Y\) in a population. Here there is no assumed covariance between sampling of unit \(i\) and unit \(j\), and the inverse probability is also the unit’s weight \(w_i\), so that an alternative specification of (1) is \[\hat{Y} = \sum_{i=1}^n w_i y_i \ .\]

The estimation procedure used by the wCorr package for the polyserial is based on the likelihood function in Cox, N. R. (1974), “Estimation of the Correlation between a Continuous and a Discrete Variable.” Biometrics, 30 (1), pp 171-178. The likelihood function for polychoric is from Olsson, U. (1979) “Maximum Likelihood Estimation of the Polychoric Correlation Coefficient.” Psyhometrika, 44 (4), pp 443-460. The likelihood used for Pearson and Spearman is written down in many places. One is the “correlate” function in Stata Corp, Stata Statistical Software: Release 8. College Station, TX: Stata Corp LP, 2003.↩︎

Sample weights are comparable to

pweightin Stata.↩︎See the “correlate” function in Stata Corp, Stata Statistical Software: Release 8. College Station, TX: Stata Corp LP, 2003.↩︎

For a more complete treatment of the polyserial correlation, see Cox, N. R., “Estimation of the Correlation between a Continuous and a Discrete Variable” Biometrics, 50 (March), 171-187, 1974.↩︎

The indexing is somewhat odd to be consistent with Cox (1974). Nevertheless, this treatment does not use the Cox definition of \(\theta_0\), \(\theta_1\) or \(\theta_2\) which are either not estimated (as is the case for \(\theta_0\), and \(\theta_1\)) or are reappropriated (as is the case for \(\theta_2\)). Cox calls the correlation coefficient \(\theta_2\) while this document uses \(\rho\) and uses \(\theta_2\) to store \(-\infty\) as a convenience so that the vector \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) includes the (infinite) bounds as well as the interior points.↩︎

The population standard deviation is used because it is the MLE for the standard deviation. Notice that, while the sample variance is an unbiased estimator of the variance and the population variance is not an unbaised estimator of the variance, they are very similar and the variance is also a nuisance parameter, not a parameter of interest when finding the correlation.↩︎

See, for example, the introduction to Rigdon, E. E. and Ferguson C. E., “The Performance of the Polychoric Correlation Coefficient and Selected Fitting Functions in Confirmatory Factor Analysis With Ordinal Data” Journal of Marketing Research 28 (4), pp. 491-497.↩︎

This means that the simulation uses discrete ordinal variables (M and P) that have 2, 3, 4, or 5 discrete levels. Note that the number of levels in M and P are chosen independently so that one could be 2 while the other is 5 (or any other possible combination).↩︎

see, for example, Olkin I. and Pratt, J. W. (1958), Unbiased Estimation of Certain Correlation Coefficients. Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 29 (1), 201–211.↩︎

The R

statspackagecorfunction is used to calculate the population Spearman correlation coefficient; this results in an unweighted coefficient, which is appropriate for the population parameter.↩︎